Early Origins of Bail Around the World

The idea behind bail is simple but powerful: instead of keeping an accused person in jail while they wait for trial, the legal system allows them to go free temporarily as long as there is some guarantee they will return to court. That guarantee might be money, property, or the promise of another person who agrees to take responsibility for the accused. Although the modern bail bond industry is relatively new, the concept of bail itself goes back thousands of years and appears in many different cultures.

Some of the earliest written references to bail-like arrangements appear in ancient Mesopotamia — clay tablets from around 2,750 BCE describe a third-party guarantee of an accused person’s appearance, much like a modern surety bond (source). If the accused failed to appear, the third party would owe a sum of money or other compensation. This arrangement echoes the modern idea of a surety bond, where one person guarantees the appearance of another.

Similar practices developed in early Germanic and Anglo-Saxon communities. In these societies, the focus was often on maintaining peace within the community rather than on punishment alone. An accused person might be released to the custody of family members or local leaders, who promised to produce them at the next court session. If the accused fled or refused to appear, those guarantors could owe money or face other penalties. Over time, these informal community-based systems started to turn into more formal legal rules.

In medieval England, the roots of the modern bail system became more clearly defined. English law distinguished between people who could be “bailed” and those who could not. Local sheriffs had significant power to decide whether to release a suspect before trial and on what conditions. Bail at this time was not always about cash payments; it often involved pledges, oaths, and the promise of sureties who would stand behind the accused.

By the 13th century, English kings and Parliament began to regulate bail more closely. Concerns grew that sheriffs were abusing their power by either refusing bail to extract bribes, or granting it inappropriately in serious cases. Early statutes tried to limit these abuses by listing which offenses were bailable and which were not. This move toward standardization laid the groundwork for later legal reforms that would influence the United States and other common-law countries.

Across other parts of the world, different societies developed their own forms of pretrial release. In some regions, community elders or religious leaders guaranteed the behavior and appearance of an accused person. In others, compensation to the victim or the victim’s family took priority over holding the accused in custody. Although the details differed, the central question was similar everywhere: how can society protect both public safety and the rights of individuals who have not yet been convicted of a crime?

English Legal Traditions and the Foundations of Modern Bail

As English law evolved, it placed increasing emphasis on protecting individuals from arbitrary detention. One of the most important milestones was the Magna Carta of 1215, which declared that no free person could be imprisoned or stripped of rights without “lawful judgment” or “the law of the land.” While the Magna Carta did not create a comprehensive bail system, it expressed a powerful idea: the government needed legal justification to hold someone in custody.

Later, in the 1600s, political conflicts in England led to abuses of pretrial detention. The Habeas Corpus Act of 1679 and the English Bill of Rights of 1689 responded to these concerns and declared that “excessive bail ought not to be required,” a phrase that would later appear almost verbatim in the United States Constitution (source). These documents limited the government’s power to hold people without trial and helped establish core protections against arbitrary detention.

By the time English settlers established colonies in North America, they brought with them a mixture of legal traditions, including the right to seek bail and the expectation that bail should not be used as a form of hidden punishment. At the same time, local conditions, frontier realities, and community values helped shape how these ideas were put into practice on American soil.

The Development of Bail in the United States

The earliest American colonies adopted many of England’s bail concepts but quickly adapted them. In 1641, the Massachusetts Body of Liberties included a section on bail, specifying that certain offenses were bailable and others were not. Other colonies introduced similar rules, blending English legal language with local customs.

After independence, the new United States faced the challenge of building a national legal framework. The Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1791, borrowed directly from the English Bill of Rights: “Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.” While this language clearly restricted how high bail could be set, it did not create a universal right to bail in every case, nor did it specify exactly how courts should decide on appropriate amounts.

Throughout the 1800s, most American states developed their own bail statutes and practices. In many places, cash bail was only one of several options, and personal recognizance (release based on a defendant’s promise to appear) was common for lower-level offenses. Judges had wide discretion, and local norms influenced whether someone was likely to be detained or released before trial. At the same time, mobility increased, and communities grew larger, which made it harder to rely solely on personal reputation and community ties as guarantees.

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, these conditions helped create a space for commercial bail bondsmen. When a court required a financial guarantee that many defendants could not pay themselves, private agents stepped in to post bonds in exchange for a fee. These agents took on the risk that the defendant might fail to appear, and they developed their own strategies, from close monitoring to employing bounty hunters, to reduce that risk.

Although the commercial bail bond industry became a distinctive feature of the American justice system, it was not universally embraced. Some legal scholars and reformers argued that tying pretrial freedom to money unfairly disadvantaged poor defendants. Others believed that private bail agents performed a valuable public service by ensuring that defendants appeared in court without forcing taxpayers to bear all of the costs.

Reform Movements and the Modern Bail Bond System

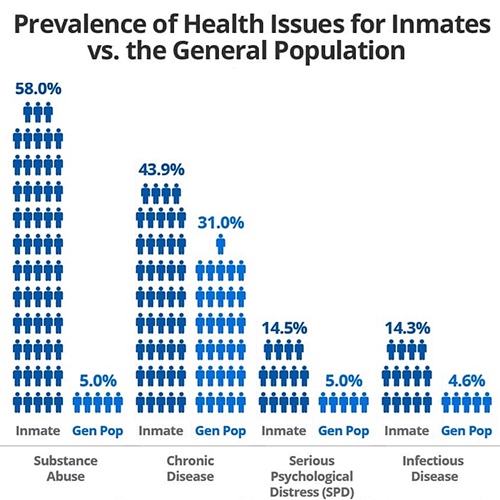

By the mid-20th century, concerns about fairness and efficiency in the bail system grew more urgent. Studies showed that many people accused of relatively minor offenses were held in jail simply because they could not afford bail, while wealthier defendants charged with more serious crimes could often secure their release. Being held in jail before trial, even for a short period, could lead to job loss, family disruption, and pressure to accept plea deals regardless of guilt.

In the 1960s, a major reform effort began with the Manhattan Bail Project, which tested whether defendants could be safely released based on factors like community ties, employment, and family relationships instead of cash alone. The results suggested that many people appeared in court without needing to pay money up front, which encouraged broader changes.

The federal Bail Reform Act of 1966 was a landmark. It emphasized release on recognizance (based on a promise to appear) for many federal defendants and sought to reduce unnecessary pretrial detention. However, growing concerns about crime in the 1970s and 1980s shifted the conversation. The Bail Reform Act of 1984 added a new focus on public safety, allowing courts to detain certain defendants pretrial if they were considered a danger to the community, even if they could afford bail.

Through all these shifts, commercial bail bonds remained a central part of many state systems. Bail agents continued to post surety bonds for a nonrefundable fee—often around 10 percent of the total bail amount—allowing defendants who could not pay the full amount to secure release. Critics argued that this model entrenched economic inequality, while supporters pointed to its role in helping people avoid long pretrial detention.

The Current Landscape of Bail Bonds Across the United States

Today, the landscape of bail and bail bonds in the United States is highly diverse and rapidly changing. Each state sets its own policies, and even within a single state, practices can vary from one county to another. Some jurisdictions still rely heavily on cash bail and commercial bail bond agents, while others have moved toward alternatives.

In recent years, several states and localities have taken steps to reduce or eliminate money bail for many offenses. New Jersey, for example, implemented major reforms that rely more on risk assessment tools and judicial discretion than on fixed cash amounts. Kentucky and a few other states restrict or do not use commercial bail bonds at all, relying instead on court-run systems of release and supervision. Illinois passed legislation to end cash bail statewide, although the details and timing of implementation have been the subject of ongoing debate and legal review.

At the same time, many other states continue to use cash bail extensively. In these places, commercial bail bond companies remain deeply integrated into the criminal justice process. They work with defense attorneys, families, and courts to secure release for defendants who might otherwise remain in jail while their cases move forward. In some communities, bail agents are long-standing local businesses and see themselves as providing an important service.

The debate over bail bonds is far from settled. Supporters of reform argue that freedom before trial should not depend on how much money a person has and that modern tools can help courts evaluate risk more fairly. They also point to racial and economic disparities in who is detained and who is released. Supporters of traditional bail and commercial bonds respond that abrupt changes can create new problems, including failures to appear and increased burdens on courts and law enforcement.

Technology is also reshaping the landscape. Text-message reminders, electronic monitoring, and data-driven risk assessments are increasingly common. Some jurisdictions now release low-risk defendants with regular check-ins rather than requiring money up front. Others are revisiting fee structures and considering ways to reduce the long-term financial impact of pretrial release conditions.

What remains constant is the underlying tension that has shaped bail systems for thousands of years: how to respect the presumption of innocence while still ensuring that people appear in court and that communities feel safe. The history of bail bonds from ancient Mesopotamian sureties to modern American debates shows that societies have always wrestled with these questions and that solutions continue to evolve.

As states experiment with new policies and reforms, the future of bail bonds in the United States will likely continue to vary from place to place. Some areas may maintain commercial bail as a central feature, while others turn toward publicly managed systems or move away from money bail entirely. Understanding the long history behind these choices helps put today’s debates in perspective and highlights the enduring challenge of building a fair and effective pretrial justice system.